Antiquariat Dasa PAHOR GbR

SUMO WRESTLING / BANDO POW CAMP, JAPAN / WOLRD WAR I:

Hans TITTEL.

相撲圖說. Sumo. Der japanische Ringkampf

[Sumo Wrestling. Sumo. The Japanese Wrestling Match]

Bando: Lagerdruckerei des Kriegsgefangenenlagers [Prison Camp Press of the POWs]  Auf Merkliste setzen

Auf Merkliste setzen

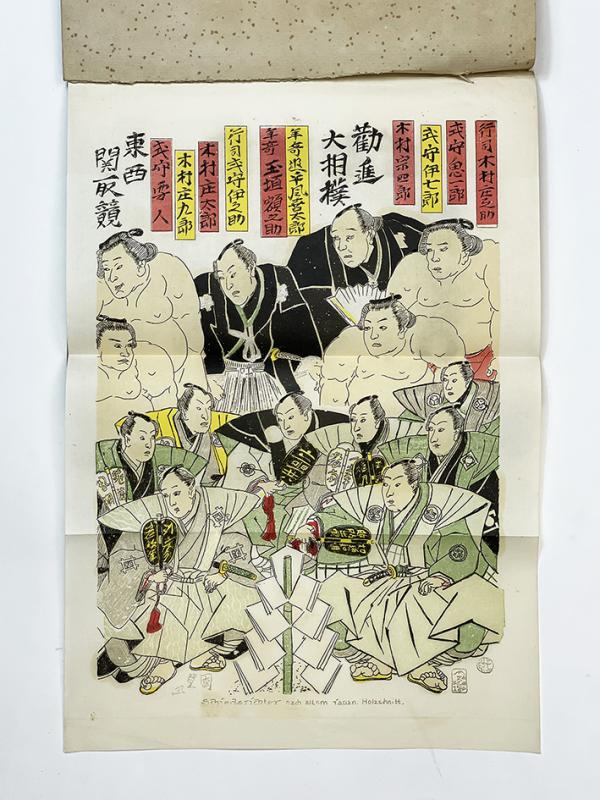

Small 4°. Folding colour image, title, 42 pp. with colour and black and white images in the text, all text printed recto on folded paper, 3 colour and 1 full-page illustration, original patterned card wrappers with mounted title in Japanese (Very Good with only minor war to the corners). [Accompanied with:] 18 black and white photos. Various sizes from 4 x 6 cm (8 photos) to 7 x 10 cm (1.6 x 2.4 inches to 2.7 x 3.9 inches), 3 photos with hand written names in pencil verso.

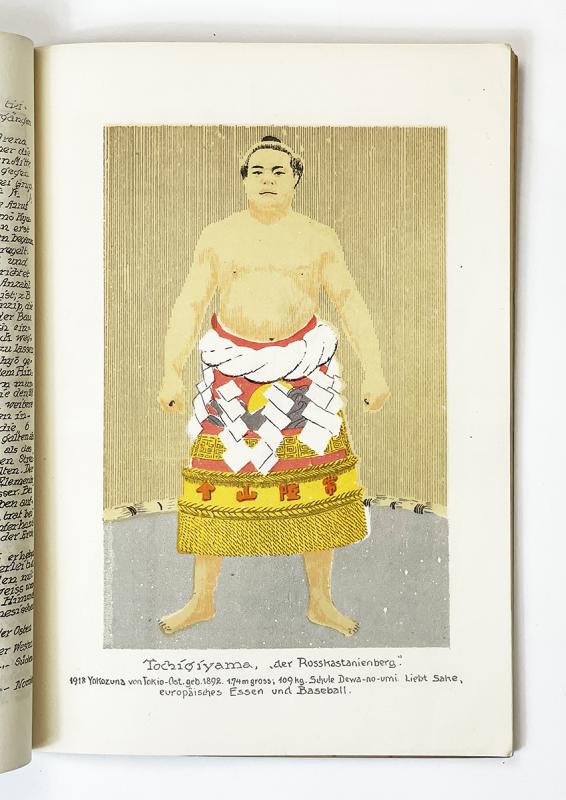

This handsomely printed Germany publication on Sumo wrestling was published as one of the last books by the Bando POW Press. It contains a lengthy description on the history of the Sumo wrestling, the techniques and depicts contemporary Yokozuna Tochigiyama Moriya (1892 –1959), Ōnishiki Uichirō (1891 –1941) and Ōtori Tanigorō (1887-1956), as well as two images, based on the older Japanese images. The cover and binding of the publication, unusual for the Bando press, mimics Japanese books. The book is accompanied with 18 original black and white privately made photographs, which showcase Sumo wrestlers, among others Tochigiyama Moriya, during the preparations. After the war the author, Hans Tittel, wrote a book on the Chinese book trade, which was published in Tokyo on 1927 and 1928. Worldcat lists three institutional examples, all in German libraries (Zentralbibliothek der Sportwissenschaften der Deutschen Sporthochschule Köln, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Kunstbibliothek, Staatsbibliothek Zu Berlin). References: OCLC 249819518. The Bando Camp, Japan: The Most Pleasant POW Camp in the World The Pacific theatre of World War I is today a largely forgotten aspect of the conflict. Prior to the war, Germany controlled several territories in the Asia Pacific region, including Papua New Guinea, the Caroline Islands and the treaty port of Qingdao (also Tsingtao), a port city in Shandong province, China, which is still today known for its beer and Wilhelmine architecture. Since 1898, Qingdao had been, in essence, a German colony, although it was not technically a possession, but rather a leased city. By eve of the war the city had developed a small, yet well-adapted and surprisingly self-sufficient German community, such that a variety of vocations from brewers to bakers to bookbinders carried out their trades in the precise manner as ordained by the apprenticeship system in the homeland. Japan joined the Entente side against Germany early in World War I, and in October 1914 dispatched a force of around 30,000 troops to take Qingdao. As most of the city’s garrison had been dispatched to Europe, Qingdao was defended by only 5,000 German troops, being mostly inexperienced civilian reservists. After an eight-day siege, the city surrendered to Japan on November 7, 1914. Qingdao’s German residents, both civilian and military, were captured and held as POWs. Initially, the German prisoners were held in variety of makeshift camps, but were eventually consolidated to six major camps within Japan. One of these camps was a Bando, founded in April 1917, near Naruto, Tokushima Prefecture (Shikoku Island). Bando was extraordinary in that the ‘prisoners’ were treated as something closer to honoured guests, held under remarkably comfortable physical conditions, and given a high degree of liberty. This was due to the fact that the camp was run by Captain Toyohisa Matsue, an ex-Samurai of the Aizu Clan. Toyohisa Matsue was deeply wedded to an ancient code, ‘Compassion of the Samurai’, that stressed that one must respect and honour one’s opponents, especially those that are entrusted to your custody. During the entire life of the Bando camp, from 1917 to 1920, a total of 1019 prisoners, almost all Germans, were held at camp. The civility of the environment was aided by the fact that only 99 of the ‘guests’ were professional soldiers; and many of the civilians were professionals with useful skills. The largest share of the Bando population was made up of merchants (303); while there were also 148 metal workers; 52 key makers; 30 farmers; 27 merchant mariners; 22 carpenters, 19 miners; 18 post and telegraph operators; and 17 bakers. Critical to our story, there were also 4 printers, 1 paper maker, 1 letter press operator, 1 lithographer, 1 bookbinder and 2 book dealers. The German officers amongst the POWs received the same salary as an equivalent Japanese officer, while other inmates received the same wages as normal Japanese soldiers. Importantly, these salaries were often accepted ‘in kind’ in the form of foodstuffs and materials. Toyohisa Matsue authorized the creation of wide variety of the recreational programmes for the inmates, including tennis, sailing on one of the camp’s ponds, swimming, a health club, bowling, orienteering and running events. The camp also had its own post office (printing lovely custom stamps that are highly collectable today), a theatre (some of the men insisted on playing women’s roles; the camp tailor made special costumes), and held many musical concerts. The local people were encouraged to associate with the inmates, and many cultural events were joint German-Japanese productions. Indeed, Bando became a highly important nexus of cross-cultural exchange, with an enduring legacy. Of great importance, the Bando prisoners introduced Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony to Japan, a piece with remains immensely popular in the country to this day. Since 1982, the city of Naruto sponsors an annual concert playing the symphony on the first Sunday in June. Following the closure of the Bando Camp, most of the prisoners were repatriated to Germany. However, 170 former inmates chose to remain in Japan, where they founded German-style businesses, some of which thrive to the present day. The Extraordinary Printing of the Bando Press Some of the most unique, beautifully designed and technically innovative printing made anywhere during the early 20th Century was created within the Bando Camp, at the ‘Lagerdruckerei’. The camp fostered a unique environment in which saw the synergy of the German apprenticeship system with Asian printing techniques and materials. The printers at the Bando camp created a press shop with the blessing and active support of Toyohisa Matsue. It helped that the camp included 10 inmates who were professionals in publishing and the book trade. Printing at Bando played major role in the daily life of the camp, as the press shop was very prolific, responsible for 50 separate titles (out of the total of 70 titles produced by all World War I POW camps in Japan). The range of publications was diverse, including newspapers, magazines, short novels, language books, economic tracts, as well as posters, flyers and invitations. Many of the books were sold outside the camp, with some even exported abroad. In the first year of its operation, the Bando press used 350,000 sheets of paper, in the second year 550,000 (an average of 1,500 sheets per day, or around 550 sheets per camp inmate!). The works of the Bando Press gained the attention of fine printing aficionados the world over, and many titles were ordered from abroad. These sales were encouraged by Toyohisa Matsue, who was proud of his camp’s products. Indeed, one of the Bando printers recalls receiving numerous letters from abroad (including a note from Frankfurt in a Red Cross box) that opined, that of all the contemporary presses across the globe, Bando was the best! The colour printing technique employed by the Bando Press is highly unusual, and this has led many to erroneously describe it as some form of the lithography. In truth, the Bando printers devised their own ingenious and gorgeous, yet labour intensive, technique that was a unique melding of German and Asian printing techniques and materials. It seems that while the technique was devised at Bando, the German printers likely benefited from having had some acquaintance with Asian papers, inks and screen-printing from their time in Qingdao. In the April 1919 edition of Die Baracke (please see the images), the Bando printer K. Fischer explains how the press’s colour printing technique was executed. He was eager to record this unique method for posterity, as Bando was shortly to be closed and the prisoners repatriated to Germany. He recalls how many of his compatriots entered the press shop in its final days, referring to his printing equipment, asking him how he expected to get “all this stuff” home? Fischer was also quite annoyed that many ignorant people referred to the Bando technique as chromolithography. He eloquently called their printing technique “a child of a prison of war” (“ein Kind der Kriegsgefangenschaft”), a procedure which could only be invented in the extremely unusual circumstances of the Bando Camp. Fischer describes the colour printing technique in exacting detail, such that it could conceivably be revived today by a highly skilled professional. While he never used the term, the technique could perhaps be described as ‘pierced silk paper colour printing’. First, the text or drawing was to be impressed upon a sheet of silk paper, that was first coated in a waterproof film, or layer, by making microscopic, strategically placed superficial perforations with a steel pin, in a stipple-like manner. The colour was then applied on the verso of the paper, before being impressed with a custom-made press. The colour then bled out through the tiny holes on the front, leaving impressions on the white paper. As the different pigments of colour possessed variable structures, they had to be applied separately in different stages: first yellow, then blue, purple, green and black. Each individual sheet of paper had to be run through the press on multiple occasions, each time to add a single colour via a signature impression from a different stencil through the silk paper. The unusual characteristic of the Bando printing is, that the used this silk-printing method also for the text. Fischer’s article is beautifully illustrated by sketches of the printing devices, as well as plates showing different stages of the same image printed in colours. The technique combines different lines and layering of colours, and Fischer patiently explains how the finest images are made. Also included is an image of the Lagerdruckerei.

6800,- EUR Sachgebiete: Japan, Orient, Sport Kontakt zum

Keine Angabe zur Besteuerung